Jessica Dauterive, Digital Historian and Music Preservationist, Fairfax, Virginia

Jessica Dauterive is a doctoral candidate at George Mason University in the History and Art History Department. She specializes in 20th century US cultural history and digital history. Before arriving at Mason, she earned a bachelor’s degree in history and a master’s degree in local public history from the University of New Orleans. Ms. Dauterive’s dissertation project, Imagining Acadiana: Cajun Identity in Modern Louisiana, explores the formation of the cultural and economic region of Southwest Louisiana that came to be known as Acadiana. It focuses on how the work of women linked historical memory to the landscape through various tourism, preservation, and folklore projects. Ms. Dauterive argues that we need to understand the development of Acadiana and Cajun identity as a project deeply embedded in the racial and cultural politics of the 20th century and one that thrived because of, not in spite of, its investment in mass culture.

At Mason, Ms. Dauterive also worked as a graduate research assistant at the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media where she contributed to various public-facing digital projects as a researcher, project manager, outreach coordinator, and collaborator. She is also working on several music history projects that consider how digital and computational methods can help us better understand sound and music archives. She currently lives in New Orleans, Louisiana, her home state, where she is writing her dissertation and working as a digital humanities consultant.

What led you to your field?

While I was an undergraduate and graduate student at the University of New Orleans, I started to understand what was possible as a historian. My mentor, Dr. Michael Mizell-Nelson, was an early adopter of digital humanities methods and encouraged his students to explore how digital tools can bring historical research to the local community. I am now a PhD candidate at George Mason University (Mason), where I have been able to grow and deepen my approach to digital history through working with the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media (RRCHNM).

How does what you do relate to historic preservation?

I come to projects as a digital historian, so I usually take on the role of providing deeper context for, access to, or increased discovery of preserved records, artifacts, or structures. When it comes to the actual work of preservation, I take the lead from librarians, archivists, and other experts. I am most excited by finding ways to use digital tools to increase public engagement with historical resources.

Why do you think historic preservation matters?

Historic preservation gives us access to materials, structures, and artifacts that help us understand who we are and where we came from. As a historian, it provides the sources through which I am able to do research and present my interpretations. For the public, historic resources can engage the senses and create a deeper connection with history than print or digital publications often can. That kind of sensory connection can be an important starting point for people to grapple with their own relationship to the past.

What courses do you recommend for students interested in this field?

I would suggest that students find courses that provide hands-on experience with preservation methods, especially if they involve working with community partners. Urban and environmental history courses can give you a deeper understanding of how race, class, sex, sexuality, and empire have shaped the development of the American landscape and guided decisions about preservation. Courses that teach practical skills like grant writing, digital methods like GIS, or research and writing skills can also be a great way to prepare for the various roles required in historic preservation work and help you figure out which role might be the best fit for you.

Do you have a favorite preservation project? What about it made it special?

As a digital public historian, I believe in the power of using digital tools to tell stories with and for our local communities. One of my favorite projects in this vein is New Orleans Historical, founded in 2012 by Dr. Mizell-Nelson in collaboration with UNO’s Department of History, Tulane’s Department of Communication, and New Orleans Center for the Gulf South. Today, it is managed by the Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies at the University of New Orleans.

New Orleans Historical is a great example of how digital methods can be used for historic preservation. The central map contains more than 500 stories about New Orleans history that can include text, audio, and visual media. Many of these stories are also curated into tours around a central theme that bring people—virtually or on foot—to different points in the city. The project draws attention not only to prominent historic sites, but also those that go unmarked, unnoticed, or that we can only recover through archival records. The project team has always collaborated with a variety of community partners and also provides undergraduate and graduate students a platform for their original research and writing.

Can you tell us what you are working on right now?

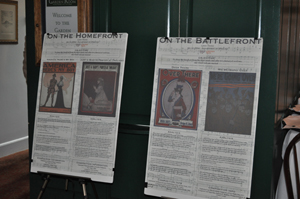

My recent digital humanities work centers on finding new ways to engage with archives of music and sound. One of the projects I’m proudest of is ReSounding the Archives, which I co-developed with Dr. Kelly Schrum at RRCHNM and Dr. Nicole Springer in the College for the Visual and Performing Arts (CVPA) at Mason. After a series of development meetings about how digital tools can “re-sound” historic sheet music, we came up with a model that addressed our intersecting interests in music history, education, and performance. Ultimately, we wanted to find a way to bring historic sheet music out of the archives and into the minds, eyes, and ears of our students and the broader public.

We secured a 4-VA research grant to develop a cross-institutional collaborative model with the McIntire Department of Music and Music Library at the University of Virginia (UVA) and the History and English Departments, School of Performing Arts, and Special Collections at Virginia Tech (VT). Music librarians and archivists helped us select historic sheet music related to WWI and provided the project with archival-quality scans of each piece. Students at UVA and VT conducted research on the songs, and their original research was included in the project to provide context for the digitized sheet music. Finally, music students at Mason and VT worked with music production students to record contemporary versions of each song. All of the materials in the site are free and available for use and reuse. We capped off the collaboration with a symposium at UVA where students performed and presented their research. We are proud of the project prototype and the collaborative model we were able to develop, and my hope is to expand on this project with other community partners in the future.

How do you think the national historic preservation programs help your community?

National recognition of and support for historic preservation can help to demonstrate the importance of these projects to the public. Most importantly, it can bolster local organizations who intimately understand New Orleans history, as well as how preservation efforts can meet residents’ contemporary needs and anticipate the challenges the city will face in the future.

Do you have advice for novice preservationists?

I think your local community can sometimes be your best classroom. Take a walk. Visit archives, historical societies, and museums. Notice what histories are preserved in your community and what might be missing. Do some research. Talk to people who are doing work you admire, and find ways to get involved.

The ACHP’s mission is “preserving America’s heritage;” can you give us an example of how your community is preserving its heritage?

I can imagine few cities that showcase the value of preservation more than New Orleans. The French Quarter is the most obvious example of preservationist efforts. Recently, I have been very inspired by the work of Paper Monuments an organization that works from a model of equity, integrity, and collaboration to integrate marginalized histories in the city’s commemorative landscape.

Why is it important to preserve historic music?

Preserving historic music allows us to better understand how technology, capitalism, race, and politics shaped and were shaped by popular culture. We can hear the different kinds of voices, musical styles, and recording technologies people listened to in the past, and think about how and why tastes have changed over time. Sometimes, music archives contain materials that are not immediately audible (a problem ReSounding the Archives was developed to address). However, by analyzing an advertisement, sheet music cover, or piece of fan mail we can uncover how audiences understood and engaged with popular culture in the past and what this can tell us about larger social, political, cultural, or economic contexts. These historical understandings can also make us sharper and more conscious consumers of popular culture in the present.

Why do you think it is important to make archives accessible to students and community members?

Making archival materials more accessible to students and community members helps to create a deeper public engagement with the past. It allows nonhistorians to engage directly in the process of doing history: asking questions, investigating those questions through primary and secondary sources, and developing informed answers. Digital tools and platforms also allow for innovative methods of discovery, presentation, and engagement that can generate new and exciting observations about the past.

Read more Q&A stories about the Preservationists in Your Neighborhood!