Richard Laub -- Director, Master of Arts: Heritage Preservation program at Georgia State University in Atlanta, Georgia

Richard Laub joined the History faculty at Georgia State University on a full-time basis in 2001 as the Director of the Heritage Preservation Masters Degree Program. Laub has worked in the field of historic preservation for more than 30 years, receiving his initial training as a restoration craftsman with the National Trust for Historic Preservation. He worked from 1987-2001 at the Georgia Historic Preservation Division, where for the last 10 years he served as the Community Planning Coordinator, providing communities and organizations throughout the state with preservation planning assistance. Active in the community, Laub has served as the Chairman of the Atlanta Urban Design Commission and has worked with his neighbors to have his Inman Park neighborhood designated a local historic district.

Richard Laub joined the History faculty at Georgia State University on a full-time basis in 2001 as the Director of the Heritage Preservation Masters Degree Program. Laub has worked in the field of historic preservation for more than 30 years, receiving his initial training as a restoration craftsman with the National Trust for Historic Preservation. He worked from 1987-2001 at the Georgia Historic Preservation Division, where for the last 10 years he served as the Community Planning Coordinator, providing communities and organizations throughout the state with preservation planning assistance. Active in the community, Laub has served as the Chairman of the Atlanta Urban Design Commission and has worked with his neighbors to have his Inman Park neighborhood designated a local historic district.

What led you to the preservation field?

After receiving my undergraduate degree in Biology, I tried many areas, even once being a baker. It was working in construction that peaked my interest in buildings. Back then, the National Trust for Historic Preservation had a restoration workshop. I applied and was accepted to learn and work at the Lyndhurst property for three years. That was my first connection with preservation. Looking at and restoring historic resources. After that, I worked at the Trust property, Oatlands in Virginia. These experiences gave me the hands on aspect needed, but I realized I was in competition with people having a master's degree. So, I went to the University of Virginia for a master's in planning with a certificate in historic preservation. I went to work for the Georgia State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO) for 14 years. There I reviewed projects with Section 106 and tax incentives and helped with community presentation, local governments, zoning, and designation processes. I taught an occasional class at Georgia State University (GSU) in planning or building materials and eventually became the director. I love it. I love working with the students and learning more about preservation.

Do you think preservation education matters? Why?

Education makes you competitive when it comes to jobs. You have the credentials for a degree or profession. At GSU we try to prepare our students for the various jobs preservationists have. I like to say, they are a mile wide and an inch deep. There are so many varied positions out there, but not many of them are available. But, preservation is a field where you can grow, change, and have many different experiences. The master's program is in the History department, so we offer a lot of classes on history and research. There are two tracks for the Heritage Preservation degree, Historic Preservation and Public History. Preservation focuses on buildings, heritage, neighborhoods, landscapes, and laws. Public History focuses on folklore, stories, heritage, production, and museum work. There are many programs in Schools of Design, Planning, or Architecture. Ours focuses on the intangible, storytelling of heritage. In 2001, the faculty wanted a Public History program. We use Heritage Preservation instead of Historic Preservation because it is more inclusive and looks at the interpretation of history outside of academia.

What courses do you recommend for students interested in this field?

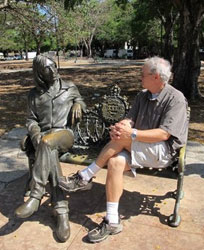

Take what you think will get you where you want to go in the future. Think outside of the program. Think about anthropology, geographic information systems, planning. These benefit city government jobs. But, look at the big picture and get what you want out of it. Study abroad! Learn what the other countries are doing. It is probably not the same kind of preservation we do here. Travel to South Africa, Cuba, Thailand, they are all so different.

Do you have a favorite preservation project? What about it made it special?

We have case study classes where we work on projects together focusing on assisting the community. We've collected information for Atlanta through historic context studies, a history of the Belt Line. In 2008, we worked on a National Register nomination for the Collier Heights neighborhood. It was the first African American post WWII suburb of its kind. It was started in the mid-1950s, and homes are still being built there. No one had created a Ranch house nomination like this before. There were 1,700 properties surveyed. We worked with GA SHPO, and it is now a local Historic District. That nomination is posted as a good example of National Register nominations on the National Park Service Web site. Something unique about the Collier Heights project was while working on the National Register district we found that most of the people who built these homes still lived in them. This was the suburban dream. The segregated areas of Atlanta were able to come together for their American Dream. We have a lot of community collaboration. We worked with a single family post war community, a 1970s community. It was fascinating to see how the buildings and community changed from a landscape filled with farms to the fastest growing area in the country.

Can you tell us what you are working on right now?

We just finished a National Register nomination for the city of Decatur that we're calling Decatur-Northwest. We are working with the Georgia SHPO for the nomination to be ready and proposed at the National Register review meeting next month. We worked with Locust Grove, a small community south of Atlanta, creating Design Guidelines for their existing and potential districts. We also created a plan for their future, such as establishing a Certified Local Government, national register nominations, designating more properties. The city of McDonough is working with us on a similar project. There is also an antebellum house in Smyrna we are creating a Historic Structure Report for. Service-learning projects not only build the confidence of the communities but it promotes students' connections with communities. These projects are very cost effective, we only ask for money to print the final products. Those small and rural communities can't afford the full cost of these projects. Right now we're working on purchasing a Rosenwald school with Henry County and Locust Grove.

Do you have advice for novice preservationists?

You need to have a passion for the purpose of preservation. If you don't have a passion then you probably won't want to be involved. There are circumstances where you might be the only person who cares about preservation and need to make the case for it. There are plenty of preservation jobs in organizations whose mission is not preservation based. You have to fight for it.

The ACHP's mission is "preserving America's heritage;" can you give us an example of how your community is preserving their heritage?

I love that! America's heritage, not America's history. It is much more inclusive and accurate. Well, Atlanta is spotty at best. Atlanta responds well to grassroots efforts, but it is not a top to bottom process. It comes from the neighborhoods wanting to be preserved. The Atlanta Urban Design group doesn't have time to get out and survey all of these places. They are preoccupied with Certificates of Appropriateness.

Read more Q&A stories about the preservationists in your neighborhood!