Laurie Kay Sommers Ph.D., Folklore, Independent Consultant

Laurie Kay Sommers, a native of Lansing, Michigan, holds a Ph.D. in Folklore from Indiana University. She currently works as an independent consultant in folklore and historic preservation through her company, Laurie Kay Sommers Cultural Consulting, LLC. She is the Co-Chair, American Folklore Society Working Group in Historic Preservation. Sommers has worked in public folklore, ethnomusicology, and historic preservation for more than 30 years for organizations such as the Michigan State University Museum, the Michigan SHPO, and the South Georgia Folklife Project at Valdosta State University. Her background in historic preservation dates to the late 1970s, when she worked for the Michigan SHPO and then as an independent consultant to the SHPO, Commonwealth Associates (Jackson, MI), and various other clients.

Laurie Kay Sommers, a native of Lansing, Michigan, holds a Ph.D. in Folklore from Indiana University. She currently works as an independent consultant in folklore and historic preservation through her company, Laurie Kay Sommers Cultural Consulting, LLC. She is the Co-Chair, American Folklore Society Working Group in Historic Preservation. Sommers has worked in public folklore, ethnomusicology, and historic preservation for more than 30 years for organizations such as the Michigan State University Museum, the Michigan SHPO, and the South Georgia Folklife Project at Valdosta State University. Her background in historic preservation dates to the late 1970s, when she worked for the Michigan SHPO and then as an independent consultant to the SHPO, Commonwealth Associates (Jackson, MI), and various other clients.

What led you to your field?

I was initially drawn to historic preservation because I loved both history and environmental conservation. Historic preservation combined both interests. My first work in preservation was a volunteer project for the Michigan SHPO on two WPA-era industrial buildings in my hometown of Lansing, Michigan. This led to a paid job completing architectural surveys and National Register nominations during the 1970s and '80s for both the Michigan SHPO and various Michigan municipalities. I applied to graduate school in both preservation and folklore. I decided on folklore since I was already working in preservation (in fact, this is how I funded part of graduate school), and felt I could always return.

After completing my PhD in folklore, I considered a return to historic preservation, but at the time (mid-1980s) the Michigan Civil Service form automatically disqualified persons with a degree in folklore (as opposed to history and architectural history, for example) from consideration for any historian position (an ironic state of affairs, since I had been one of the SHPO's preferred independent contractors prior to completing my doctorate!).

This dichotomy between folklore and historic preservation shaped my career for the next 25 years, as it has the field at large. Although I felt I had the tools and expertise to shape an integrative model of folklore and historic preservation that preserved both tangible and intangible resources, I didn't have the opportunity to do so until 2010. I became part of a team hired to complete a historic structures report for Fishtown (Leland, Michigan), a historic but still active working waterfront that combines a National Register Historic District with a distinctive cultural landscape. The Fishtown HSR was the rare project in which I was hired precisely because I had worked in both fields, and because the client, Fishtown Preservation Society, recognized the importance of folklore and ethnography to understanding, preserving, and interpreting Fishtown (http://www.fishtownmi.org).

How does what you do relate to historic preservation?

As a folklorist with a background in historic preservation, I am trying to model and encourage what I call an integrative approach to folklore and historic preservation. The preservation field is very good at preserving buildings and structures, but not so good at preserving places in a holistic sense. An integrative approach combines traditional historic preservation research with folklore methodology for a richer and more nuanced understanding of the use, significance, and meaning of place. Folklorists bring skills of oral history and ethnography - the in-depth study of a community or culture through observation and cultural documentation (field notes, interviews, video, photography, audio recordings, etc.). This is a methodology that integrates people, story, tradition, and use with buildings and landscapes.

Kingston Heath (director of the Historic Preservation Program at the University of Oregon) has called for a more "humanistic" approach to historic preservation, whereby "buildings and settings, alone, do not make place - people, in their interrelationship with the natural and built environments, make place." This is what integrating folklore and historic preservation seeks to accomplish. Places matter because they are meaningful to the people who use them, and meaning derives from tradition, memory, and story, not from historic archaeological sites and architecture alone. Folklore methodology provides a key to understanding and preserving places that matter.

Why do you think historic preservation matters?

Historic preservation, long touted as an economic development strategy through adaptive reuse, is increasingly become a "green" strategy, as the carbon footprint of "tear-downs" and new construction becomes environmentally unsustainable. Preservation is also an essential component of placemaking, as the National Trust's Main Street and Places that Matter programs, as well as Citylore's Place Matters, have long understood. Cultural landscapes and their preservation are increasingly important as development threatens farmscapes, ranch lands, working waterfronts, and other landscapes across the country. Historic preservation remains integral to creating "cool cities" attractive to Millennials and others because of their character and sense of place. And through Section 106, historic preservation remains an important tool for communities to protect against or mitigate the destructive effects of development projects of all kinds.

What courses do you recommend for students interested in this field?

Students interested in historic preservation need to prepare themselves as broadly as possible so they can forge creative partnerships with existing and new stakeholders in preserving and protecting vibrant historic places. Courses in oral history and ethnography - often beyond the scope of most current preservation programs - will enhance understanding of context, use, place, meaning - and how to document and preserve it. Young preservation architects need to study "green" architecture, LEED standards, and how to retro-fit existing structures to make them more usable and sustainable.

Do you have a favorite preservation project? What about it made it special?

My favorite preservation project is in Fishtown (Leland, Michigan), facilitated by the pioneering work of Fishtown Preservation Society, Inc., where I was the historian/folklorist and lead writer for The River Runs Through It, Report on Historic Structures and Site Design in the Fishtown Cultural Landscape (2011). The Fishtown HSR combines traditional historic preservation research with ethnography, oral history, and a cultural landscape study while documenting and assessing the physical conditions of the structures and site, and proposing treatment alternatives.

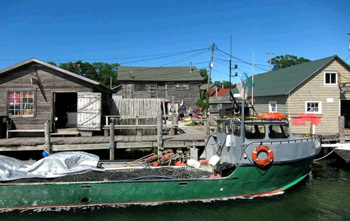

Fishtown, Leland, Michigan, showing the trap-netter Joy, two historic fish shanties to the left and right, and the historic ice house in the center. Photo by Laurie Sommers, 2010, courtesy Fishtown Preservation Society, Leland, Michigan.

In February 2007, Fishtown Preservation Society, Inc. (FPS), an IRS Section 501(c)(3) organization, acquired a quarter acre tract on the Leland River in Leland, Michigan. The purchase included eight shanties, two smokehouses, two commercial fishing vessels, 200 feet of docks along the Leland River and other ancillary buildings in the area known as Fishtown. Fishtown has been the locus of Great Lakes commercial fishing activity since at least the 1860s, one of the region's most visited tourism sites, an essential engine of the local economy, and a historic preservation jewel (part of the Leland National Register Historic District listed in 1975). Many of Fishtown's historic shanties now house low impact retail establishments, but the area is still a working waterfront. It is rare to find working commercial fisheries on the Great Lakes. It is rarer still for a working fishery to be so accessible to the public, operating in situ, in historic shanties that have housed generations of commercial fishermen. It is a survivor, a place of incredible beauty, and rich in stories and traditions that nurture people's attachment to the place.

Fishtown during the peak fishing period, 1920s.

Photo courtesy of Leelanau Historical Society.

Since its inception, FPS has followed two complementary strategies in its stewardship of Fishtown: 1) careful attention to developing sound historic preservation planning documents; and 2) an integrative historic preservation model that incorporates folklore methodology (ethnography/oral interviews) in order to achieve a richer and more nuanced approach to place-making and preservation. These paired approaches reflect the expertise of FPS Executive Director Amanda Holmes (a folklorist with training in historic preservation) and Kathryn Bishop Eckert, retired Michigan SHPO, both of whom recognized the value of this more holistic approach in preserving structures and their meaning.

The integrative approach addresses exactly what makes Fishtown so special. This is a place where multiple generations of commercial fisherman lived and worked (and still do), continually patching and adapting their modest vernacular wood shanties, ice houses, and net sheds; passing on knowledge of their trade from father to son; and sharing stories of experiences on lake and shore. As the Leelanau Enterprise observed in 1904, "The fishing season will soon be over, but not the yarns." Multiple generations of tourists, artists, and summer residents also have formed deep attachments to Fishtown, purchasing fresh fish, observing and painting the rich textures of shanties, fish nets, waters, sky, and boat. The memories and experience of all these stakeholders - many recorded in oral interviews - are essential to creating and understanding the meaning and significance of the place to those who love Fishtown. Along with a wonderfully evocative array of historic photos and other archival documents, they flesh out the chronology of development and use of these modest, weathered, well-used shanties, bringing to life what the fishermen did there and uncovering the nexus between architecture, place, and community life.

Perhaps most special of all, Fishtown is a place where you can still experience Michigan's Great Lakes maritime heritage with all your senses. Carlson's Fishery, the surviving commercial fishing operation, is the heart and soul of Fishtown and its most significant structure. Because of it, the air is pungent with maple smoke and the aroma of smoked fish. Fishermen still catch and process fish in view of visitors and answer questions about their increasingly threatened occupation. My documentation included photos and interviews about fish processing and smoking in Fishtown today, in addition to the chronology of development of the buildings themselves. Fishtown Preservation Society used research consolidated in the HSR when developing an interpretive plan and installing signage that further engages visitors in Fishtown's commercial fishing heritage.

Nels Carlson (left) and Alan Priest place fish on the smoking racks at Carlson's Fishery. In 2012 Nels Carlson became the fifth generation of his family to own the historic fishery building, now the sole remaining commercial fishing operation in Fishtown. Photo by Laurie Sommers, 2010, courtesy Fishtown Preservation Society, Leland, Michigan.

Can you tell us what you are working on right now?

One current project is to continue the activities of the Working Group in Folklore and Historic Preservation, a policy initiative of the American Folklore Society. Our goal is to better position folklorists and folklore methodologies as central forces in historic preservation. I authored the white paper, "Integrating Folklore and Historic Preservation Policy: Toward a Richer Sense of Place" and developed the associated Web site that has case studies of projects that involved folklore and historic preservation, as well as a bibliography and webography. A particular emphasis of the working group has been to develop model Traditional Cultural Places nominations to the National Register of Historic Places, in particular nominations that expand the purview of Traditional Cultural Places to include more than sites associated with American Indian, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander. Fellow folklorists Beth King (Wyoming) and Tina Bucuvalas (Florida) have worked on successful nominations for the Green River Drift (cattle trail) and Greektown in Tarpon Springs. We also seek to network with like-minded folks in allied fields and to engage young people in our work.

How do you think the national historic preservation programs help your community?

Since I consider Fishtown as my community (although I don't live there), I'm sharing some narrative provided by colleague Amanda Holmes, director of Fishtown Preservation Society. The work of FPS illustrates how a variety of national organizations have helped in the preservation and stewardship of Fishtown.

Immediately after acquiring Fishtown, FPS applied for and was granted Michigan Coastal Zone Management funding to initiate research for an Incremental Historic Structure Report and for a Preliminary/Conceptual Site Design and Plan, completed in January 2009 as the Fishtown Site Study, Design and Master Plan (the "Master Plan"). FPS began with an Incremental HSR because we knew that, though we did not have the means for the full undertaking at the time, gathering our historical resources from the start would benefit the eventual study.

During the same period, an extensive collection of oral histories was supported by a 2008 NOAA Preserve America Initiative Grant. This project became the seed for all subsequent research on the site and structures, establishing experience and memory - particularly of Fishtown's fishing heritage - as integral to any planning and preservation decisions.

Building on the momentum of the Fishtown Master Plan, FPS applied for and received several subsequent grants for more comprehensive planning projects called for in the Master Plan. The receipt of a $50,000 Jeffris Heartland Fund grant from the Midwest Office of the National Trust for Historic Preservation for a Historic Structure Report (HSR) for Fishtown set the stage for another succession of projects. In 2009 the Michigan Coastal Zone Management Program stepped forward with $40,000 to help fund the construction drawings and specifications for the buildings in Fishtown as well as work on the Fishtown Long-Range Interpretive Plan. Most of the work on the Interpretive Plan has been provided by a grant from the National Park Service Rivers, Trails & Conservation Assistance Program, with the NPS providing the expert services of one of their planners in assisting the FPS Board and volunteers to develop that plan, which was completed by the end of August 2011.

In 2011 FPS received a major grant from the Michigan Humanities Council for the implementation of the short-term elements of the Fishtown Long-Range Interpretive Plan, which included on-site exhibits, an intern, and the publication of a book, Fishtown, Leland Michigan's Historic Fishery, that utilizes the research materials gathered for the HSR but in a format that reaches the broader public. This book, published in 2012, was named a 2013 Michigan Notable Book by the Library of Michigan.

Do you have advice for novice preservationists?

-

Take advantage of existing internships - or try to create new ones with organizations of particular interest. This can provide valuable training and professional contacts prior to formally entering the job market.

-

Consider volunteering to build your resume. I volunteered the summer after I graduated from college, and it opened all sorts of doors. Think broadly and creatively about potential partners in your work.

-

Take a look at the approaches to preservation, landmarking and advocacy by Citylore's Place Matters in New York City where the starting point is the local community's definition of what is significant and worthy of preservation (often buildings not eligible for the National Register). (http://placematters.net/)

-

Don't forget the people, stories, uses, and the meaning of the places you seek to preserve. It's not just about the building.

-

Know that you are doing important work in placemaking, economic development, and sustainability.

The ACHP's mission is "preserving America's heritage;" can you give us an example of how your community is preserving its heritage?

My hometown of Lansing, Michigan, has been an auto town since Ransom E. Olds built his first gasoline-powered vehicle here in 1897. After a brief foray in Detroit, in 1901 he returned his Olds Motor Works (later Oldsmobile) to Lansing. Shortly afterward, Olds left that company and founded REO Motor Car Company (1904-1975) and continued with REO for many years. His original Olds Motor Works was bought by GM in 1908, and Lansing has been a GM town ever since. Happily for the local economy GM still has two viable Lansing plants, although much of the area's tangible and intangible automobile heritage has been lost. Fortunately, successful examples of adaptive reuse are preserving the tangible heritage. One notable example is the Motor City Lofts, which have converted the historic W.K. Prudden Company factory (vacated in 1974) into contemporary downtown living space. The Prudden Company was the world's largest producer of both wood and steel wheels, and one of the major reasons that R.E. Olds moved his company back to Lansing in the early 1900s. Lansing is also preserving the area's intangible auto heritage, especially through the work of the Motor Cities National Heritage Area, "an affiliate of the National Park Service dedicated to preserving, interpreting and promoting the cultural and historic landscape associated with the automobile in Southeastern and Central Michigan." (http://www.motorcities.org/) Among its exciting heritage preservation initiatives are the Wayside Exhibit Program that will create 250 outdoor exhibits commemorating the region's automotive history. (Lansing already has signage as part of this program, see http://motorcities.org/programs/wayside/lansing/.) Additionally, a grant from Motor Cities to Michigan State University's renowned Voice Library will fund digitization of a large body of oral histories with local auto workers into "The Lansing Auto Town Gallery." I'm proud that Lansing is an exemplar of this holistic approach to heritage preservation.

How does folklore play a role in historic preservation?

Folklorists in the past often did not find their skills valued or welcomed in the world of historic preservation and Section 106 review. This was certainly not always the case, but when I was working for a cultural resources management firm as a "historian" (at the same time I was a graduate student in Folklore), I would have cost the company extra money by including ethnography in my reports: this would have been considered nice but definitely not essential. A colleague who did survey work in the wake of Hurricane Katrina was told that he was to focus on buildings only, not people and their stories/memories of place. From a folklorist's point of view, that was a travesty. What are we preserving? If historic preservation is interested in preserving "place" in its broadest and richest sense, then folklore has much to contribute:

-

As placemaking (and the historic preservation community's place within it) gains momentum at local, state, and national levels in both public and private spheres, the folklorist's methodology can lead to a richer sense of place through ethnographic documentation of context and use - the ways story, ritual, and behavior link communities to places and make them meaningful.

-

As Section 106 and environmental review continue to be major activities for CRM firms and SHPOs, some preservationists are realizing that ethnography - long a weak point in environmental review efforts - is important to the process. Folklore methodologies can help engage the local community and elicit their voices.

-

As the National Park Service revisits National Register Bulletin 38 (Traditional Cultural Properties or TCPs) and seeks to clarify its parameters, folklorists are creating model nominations for a range of places, beyond the sacred American Indian, Pacific Islander, and Native Hawaiian places that are typically listed as TCPs.

-

Folklorists are expanding the range of properties and places typically listed in the National Register to include a wider range of cultural communities and a greater diversity of buildings, structures, and places (think a traditional Wyoming cattle trail, Tarpon Springs' sponge fishing docks, an Italian American religious shrine in Staten Island). This in turn is providing a richer and more inclusive documentation of our heritage.

-

As the National Park Service pays increasing attention to cultural landscapes, folklorists can assist in the understanding and documentation of cultural traditions, responses to the natural environment, and land use and activities, all landscape characteristics highlighted in National Register Bulletin 30 (Rural Historic Landscapes).

-

As the historic preservation movement increasingly embraces diversity and the vernacular, folklorists can bring our skills to bear. Model programs like Citylore's ground-breaking Place Matters have integrated folklore, historic preservation, advocacy, documentation, and grass roots participation by focusing on New York City's culturally and historically significant places, not necessarily the architecturally significant sites typically included in the National Register. (http://placematters.net/)

Read more Q&A stories about the preservationists in your neighborhood!