Kelly G. Marsh (Taitano), Professor and Cultural Preservationist

One of the larger surviving sets of latte at the Senator

Angel L.G. Santos Latte Park, Hagåtña, Guåhan (Guam).

Photo: Taken by Ronald Laguana.

Kelly G. Marsh (Taitano) holds a doctorate in cultural heritage studies from Charles Sturt University, Australia, building on her BA in history and anthropology and MA in Micronesian studies from the University of Guam (UOG). She authored the political review of Guam for the Contemporary Pacific: A Journal of Island Affairs for 11 years and remains active in local cultural and historical efforts. Some of this activity includes serving as the Chair for the History Subcommittee of the 12th Festival of Pacific Arts 2016 which Guam hosted; conducting applied research within the Mariana Islands; and teaching Hestorian Guahan (History of Guam) and special studies courses at UOG such as Fa'tinas i Latte, the first latte carving and quarrying course offered by the university’s Chamorro Studies program co-instructed with latte carver Joe Viloria and a host of guest contributors like former course participants Moñeka De Oro and Daniel Stone.

What led you to your field?

Mapoksai yu' gini Guå han (I was raised on the tropical island Guam), a child of two civil servants who ventured here in the ‘60s as teachers. I grew up swimming by the island’s beaches, roaming its jungles, and visiting its cultural, natural, and historical sites. An avid reader growing up, I realized that the types of books I most enjoyed reading were those that exposed me to history and culture through the eyes of the people. That led me to earning a double major in history and anthropology as an undergraduate, a master’s in Micronesian Studies, and a PhD in Cultural Heritage Studies. Those classes taught me to better appreciate the history of our island and region, the significance of each historical layer of our cultural and historical sites, the value of listening to oral narratives associated with sites that provide much of their significance, and the need for ensuring that these elements are transmitted to our island youth and others. I’m proud to say that I’m a product of the island in many ways, including much of my university education and the work I have done alongside the many who have grown up to care about our community and advocate for its safeguarding and promotion locally, nationally, and internationally.

The poster that re-envisions the ancestral village of

Litekyan (Ritidian) around 1680s, shortly after the Spanish

arrived in Guåhan (Guam) to introduce the Catholic faith.

One of our goals was to demonstrate that for more than

100 years after initial contact, ancestors were continuing

to live traditionally.

How does what you do relate to historic preservation?

In caring about Guåhan and the other 14 islands within Låguas, or the Mariana Islands, as the homeland of the Indigenous CHamoru people (as well as for Refaluwasch [Carolinians] in the Northern Mariana Islands) say, and in listening to our historic preservation specialists, it became clear that there was a need to bridge the gap between academic research and other professional work (archaeological, historical, horticultural, etc.) and our island community members. Figuring out ways to bridge those gaps allows our communities, which thirst for knowledge about CHamoru (and Refaluwasch) ancestors, to directly benefit from decades of information that is locked away in a sense within technical reports, academic articles, and the oral archives of cultural practitioners and traditional island historians. In partnership with CHamorus, Refaluwasch, and local community members that have made Guåhan or another Mariana Island their home, I have sought ways to transmit such knowledge in engaging and accessible ways to our community and to visitors and others alike. Applying my various trainings and based on the latest academic and cultural understandings, we have created educational posters, brochures, elementary and middle school level books, interactive e-books, and coloring apps (some of which are free to download within the US at http://itunes.apple.com/us/book/id1242381931 and http://itunes.apple.com/us/book/id1242393865, with more to come in android formats). We have also joined efforts to develop a university class meant to recapture the “lost” tradition of quarrying and carving latte, which are unique to the CHamoru people as described more fully below. Those in the latte project make sure to conduct outreach programs, often with hands on application, to the youth via the museum, at our local festivals, and in the schools.

Why do you think historic preservation matters?

Fellow community advocates and myself feel that the historic preservation projects that our island communities are working on are incredibly important in this day and age of rapid modernization, globalization, cash-based economies, and relatively recent dramatic shifts in our island community demographics. This latter condition means that CHamorus currently constitute just 42 percent of their island homeland’s population whereas in 1941, they still comprised 91 percent of the island population. All of these conditions challenge traditional cultural identities, the transmission and practice of cultural knowledge, skills, and behaviors, and the health and wellness of our communities. Though we have numerous examples of CHamorus excelling as lawyers, Disney executives, Brigadier Generals, entertainers, professional athletes, owners of restaurants and food trucks that specialize in local foods (look for them in your state!), and much, much more at local, national, and international levels, it is also true that, in their homeland islands, CHamorus suffer some of the highest rates of health issues like diabetes and heart disease, and other challenges to their quality of life. Historic preservation efforts have the potential to be part of the solution in addressing those issues when those efforts focus on projects that showcase, educate, and recapture knowledge about the CHamoru history and culture. Historic preservation efforts can also allow for helping the community at large better understand and reflect upon the other layers of history that sit aside the 3,500 years of CHamoru connection to their ancestral lands.

An important aspect of teaching a course about latte

carving and quarrying has been working closely with

cultural practitioners. Joe Viloria (far right) has been a

co-instructor for the course and is imparting carving

methods to Unibetsedåt Guåhan (University of Guam)

students, Fall 2015. Photo: Taken by Kelly G. Marsh.

What courses do you recommend for students interested in this field?

There is so much to be gained in multi-disciplinary approaches. There are many academic fields, professions, and types of cultural knowledge that can equip people to carry out the kind of historic preservation outreach that I've discussed above. Anthropology, Archaeology, History, Regional/Cultural Group Studies, Heritage Studies, and Historic Preservation are good bases to partner with your particular interests be they Accounting, Business, Social Work, Traditional Mediation, Environmental Studies, Indigenous Sciences, Modern or Traditional Medicine, or something else. They each have the power to contribute to the recognition and commemoration of our heritage and histories, and to contribute to their safeguarding for and transmission to our children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren.

Several sets of latte at Litekyan (Ritidian) in northern

Several sets of latte at Litekyan (Ritidian) in northern

Guåhan (Guam) are still in situ (in place). This particular

set is one of the few that are no longer standing but much

can be learned from them. Litekyan is one of our oldest

known sites in the archipelago, having been used as far

back as 3,500 years ago. It is a powerful place with a lot

of information still to share about life before, during, and

after ancestors lived in latte villages. Photo: Taken by

Amber Rose Baynum.

Do you have a favorite preservation project? What about it made it special?

Particularly satisfying was the effort to re-envision the ancestral village of Litekyan, Ritidian, in northern Guåhan. Years earlier, I had heard people say that because of the lack of historical records and the disruption of traditional knowledge due to the particular history of missionization and colonization in Låguas (the Mariana Islands), CHamoru villages could not ever be adequately represented. However, with the dynamic revitalization of the CHamoru culture and the decades of research that have occurred here, we were able to take that archaeological, cultural, geographical, historical, horticultural, linguistic, and seafaring knowledge to map out a re-envisioning of one of our oldest and most significant ancestral villages. The re-envisioning portrays not only the physical location of houses and other known or theorized features, but core cultural values and lifeways. We printed 1,000 copies of it as large posters, and provided them to every local school and public library as well as relevant governmental and other offices. People continuously remark on how much they appreciate being given that gift of re-envisioning that part of their heritage which they may not have necessarily been able to do as comprehensively as before. Since we developed this with image editing software, we have the capacity to revisit our work and update it as new understandings come to light. Not only was it satisfying to provide that to the community, but I shall always treasure the friendships and working relationships that developed from the work of that project; relationships that will come into play again and again as we each continue to move community causes forward within our various fields.

Student carved latte are on display at the University of

Guam. This display was purposeful in not only showcasing

efforts toward recapturing a tradition, but was an opportunity

to demonstrate that latte were carved in a range of sizes and

styles as discussed on the exhibit sign. These latte were

modeled on a set in the island of Pågan, several islands

north of Guåhan (Guam) within the Mariana Islands

archipelago. Photo: Taken by Kelly G. Marsh.

Can you tell us what you are working on right now?

Currently, I am working on two projects, both related to latte. One is continuing to work with CHamoru and local partners, passionate university students, and island youth to recapture the “lost” tradition of quarrying and carving latte (CHamoru house pillars out of stone). We were inspired in that we have seen CHamoru seafaring traditions, also “lost” for more than 200 years in the onslaught of colonization and modernization, once again thrive. Sakman, duduli, and galaide (different classes of CHamoru sailing vessels) now ply our waters and grace island canoe houses. Through our work, latte are once again being added to local landscapes and recapturing not only the skills, methods, and knowledge of the tradition, but people’s imaginations. Despite the deep cultural and spiritual significance of latte to CHamoru and outside interest in one of the most visible types of heritage left behind by I Manaotao Mo'na (CHamoru ancestors), very little about latte is understood by a good portion of our island community. With this in mind, a fellow colleague and I are developing a highly visual coffee table book that harnesses decades of historic photographs and is written by experts but for a general public readership. We have become quite excited about the contribution that this book will be as we engage in lively discussions with cultural practitioners and various historic preservation experts, comb through historical photo collections and archaeological reports, and envision what will most benefit the latte heritage itself and the community.

A class site visit to the largest latte were ever crafted

(though they were never completed) in a neighboring island,

Luta (Rota), Mariana Islands. The latte would have stood

perhaps as tall as 20 feet when completed. Students

(L to R) Daniel Stone, Joy Atalig, and Andrew Gumataotao

and Instructor Kelly G. Marsh.

How do you think the national historic preservation programs help your community?

The U.S. territorial Government of Guåhan has a Division of Historic Resources that serves as our State Historic Preservation Office. Through the years, national historic preservation programs have provided funding and other support in our local efforts to protect, maintain or preserve, and promote our local heritage. Within the Pacific, we meet regularly with similar territorial and freely associated historic preservation offices from American Samoa, the Northern Mariana Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, and the Republics of Palau and the Marshall Islands and with national historic preservation officials to inform, support, and encourage each of our sets of heritage endeavors. Many people within our island communities have shared that they are particularly grateful to U.S. federal historic preservation programs for having formally introduced the concept of modern preservation while being mindful to work at harnessing such programs in ways that do not conflict with, challenge, or silence local cultural values.

Do you have advice for novice preservationists?

Roll up your sleeves, figure out your interests, and get engaged. Those are key ingredients to expanding your knowledge and making a difference. Look for trainings and internship programs that may be available in your area held by parks, historic preservation offices, or historic societies. Cultural practitioners and historic preservation experts are often responsive to authentic efforts to support causes that benefit the communities at hand. As with any culture or group of people, there can be sensitivities and competing perspectives. What is important are good faith efforts to respectfully and thoughtfully safeguard, commemorate, or promote heritage coupled with the desire to listen and understand that one is facilitating an action on behalf of something bigger than themselves as individuals.

The ACHP’s mission is “preserving America’s heritage;” can you give us an example of how your community is preserving its heritage?

GuÃ¥han’s community has long worked toward recognizing and preserving its heritage formally and informally. In addition to nominating sites to the National Register of Historic Places each year, sites are inducted into the Guam Register of Historic Places. We have registered a number of ancestral CHamoru sites as well as sites that recognize more recent CHamoru achievements. These include sites where CHamorus and locals advocated for U.S. citizenship after being held as wards of the United States for some 50 years; or which represent an important step forward in the people of GuÃ¥han’s progression of being afforded what are still limited civil rights by the U.S. federal government; or that demonstrate the blending by CHamorus of Spanish and early American house construction styles (GuÃ¥han was under a Spanish colonial administration for 200 years and was ceded to the United States in 1898, after Spain lost the Spanish-American War). Our registers represent other elements of our history as well, such as that of being one of just a few inhabited U.S. areas that suffered an enemy occupation during World War II (1941-44). Our community is fortunate to have a very active semi-autonomous government entity, the Guam Preservation Trust (GPT). GPT has contributed greatly to our island’s historic preservation causes - holding preservation trainings, rehabilitating some of our most special cultural and historical sites, commissioning research, and supporting various types of grassroots historic preservation efforts. For numerous years now, GPT has supported a Guam History Day competition on island and each year since, we have sent winning island youth to participate in the National History Day competition in Washington D.C., where several of our winners have done quite well. We are also fortunate to have local organizations and community members who promote historic preservation causes among our island youth and our community at large.

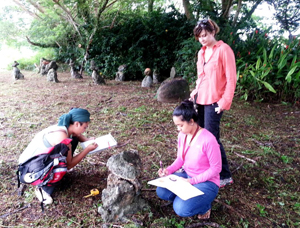

A class site visit to the village of Talofofo, Guåhan (Guam)

where students Moñeka De Oro and Tammy Mangloña

are documenting a small set of latte.

How do writing and teaching play a role in historic preservation?

Writing, developing public presentations, and teaching are serious endeavors that incentivize people such as me to work toward deeper understandings of issues. Writing gets the information one has been gathering out to a broader public and enter into the larger community and academic conversations. Teaching in Indigenous and local communities such as we have on Guåhan allows for valuable dialogues to occur. As a university professor, I share academic knowledge and theories while students, each from different families or sectors of the island community, share family history, village perspectives, and on-the-ground community realities. In class, we each learn about the layers of history which I encourage students to see themselves in and to understand the importance of their being the link in the generational chain of knowledge in transmitting the history of the people, cultures, and places of our island. Some of what they find most memorable are projects I assign to gather oral history from elders or to visit registered cultural and historical sites to make observations.

Students in Summer Session Fa'tinas i Latte University

of Guam course conducting a site visit to the Senator

Angel L.G. Santos Latte Park. Eva Cruz to the far left

is leading the blessing and honoring of the ancestors

along with Moñeka De Oro, Amber Rose Baynum,

Adrian Davis, and Selena (not pictured Chlesea Aquai).

Photo: Taken by Kelly G. Marsh

What is the significance of latte?

Latte are significant in several ways. They are unique to the CHamoru people, while at the same time, they demonstrate their deep ancestral ties to other peoples within Island Southeast Asia and the Pacific with similar wooden and stone pillars. What makes latte unique is that they are two-piece stone pillars consisting of a purposely formed or selected tåsa (capstone), thought to have an architectural function, and haligi (pillar base). Latte supported superstructures such as houses and possibly guma’ uritao (men’s houses) from perhaps as early as AD 800 or 900 to at least the early 1700s. Latte are associated with ancestral spirits not only because CHamoru ancestors crafted the stone pillars but because burials occurred at times near latte-supported structures. Latte are thus felt to be associated with or to house the ancestral spirits of the household. Thus, CHamoru and others continue to ask permission before entering area with latte and may leave an offering to demonstrate respect toward the ancestral spirits present. Latte which range in height from two or three feet to 16 feet,are some of the most visible elements of ancestral heritage in a tropical climate where much has not survived the test of time. Further, they demonstrate remarkable early CHamoru engineering achievements (a few of which are said to be larger than stones used for constructing pyramids). As such, latte have become iconic symbols of CHamoru identity. They are replicated or otherwise referenced in innumerable ways - in modern architecture, art, jewelry, tattoos, car decals, imprints on clothing, and more. If you look carefully, you may note the latte symbol in your area on someone’s t-shirt, hat, or car as CHamorus and former Guam residents live in every state in the U.S. and likely every U.S. territory as well.

Read more Q&A stories about the preservationists in your neighborhood!