Juliet Cutler, Interpretive Planner and Exhibit Developer, Atlanta, Georgia

Juliet Cutler, principal at Nomad Studio, has developed more than 40 interpretive plans a nd exhibits for visitor centers, museums, historic sites, and cultural destinations around the world. As a talented planner, writer, and educator, Ms. Cutler is gifted at understanding visitor demographics and needs, identifying core messages, and developing creative and appropriate strategies to convey those messages in ways that transform research and facts into compelling story-based narratives and engaging visitor experiences. Her work demonstrates her commitment to helping clients achieve meaningful connections with people and powerful links to places through interpretation.

nd exhibits for visitor centers, museums, historic sites, and cultural destinations around the world. As a talented planner, writer, and educator, Ms. Cutler is gifted at understanding visitor demographics and needs, identifying core messages, and developing creative and appropriate strategies to convey those messages in ways that transform research and facts into compelling story-based narratives and engaging visitor experiences. Her work demonstrates her commitment to helping clients achieve meaningful connections with people and powerful links to places through interpretation.

Known for her sensitivity to diverse perspectives and her ability to facilitate a common vision, she has worked with communities throughout the world including several Native communities such as the Maasai, Inuvialuit, Cherokee, and Caddo, to name a few.

Even beyond her work with clients, Ms. Cutler regularly publishes her writing. Her publications now number more than two dozen, and her first book Among the Maasai, an account of her experiences working in Tanzania to empower Maasai girls through education, is forthcoming in September 2019.

She is a certified interpretive planner (CIP) and a certified interpretive trainer (CIT) through the National Association for Interpretation. She has a Masters in communications development and English from Colorado State University and a B.S.Ed. in English and communications from the University of North Dakota.

What led you to your field?

I grew up in Montana with a deep connection to that place—its beauty and history. As an adult, I sought to protect important landscapes and historic sites because I recognized that these finite, tangible resources hold the stories of not only who I am, but also who we all are. I wanted people to recognize and care for the important places in their own communities, and I believed this was possible when people understood the value of these places on a personal level. At heart, I am a storyteller and a teacher, and this led me to interpretation, which is about revealing important stories and educating people about significant places.

How does what you do relate to historic preservation?

For the last 15 years, I’ve had the privilege of designing interpretation and exhibits for clients around the world. The goal of nearly all of these exhibits has been to engage visitors as stewards of important natural, cultural, and historical resources. I’ve found the best way to do this is through powerful storytelling. When I design an exhibit, I seek to make a story three dimensional, to bring the past to life, and to engage visitors in the story. Storytelling is embedded in the human experience, and it often reaches people on a level that facts and figures simply can’t. When a story touches a visitor, then they become invested and want to be caretakers of the resources.

Why do you think historic preservation matters?

Simply put, if we don’t preserve the tangible remnants of our past, then we begin to lose our history.

What courses do you recommend for students interested in this field?

For professionals already in the field who want access to continuing education courses, I would check out offerings from the American Alliance of Museums (AAM) and the National Association for Interpretation. The annual conferences for both of these organizations are worth attending.

For students, I would look for museum studies programs in your area. AAM has a great tool for finding courses at http://ww2.aam-us.org/resources/careers/museum-studies. The most practical and important courses in my experience have been a graphic design course, a program design and evaluation course, and a stakeholder engagement course.

Do you have a favorite preservation project? What about it made it special?

I recently developed guidelines for interpretation for the Bureau of Land Management (BL M) in Wyoming. The BLM manages several historic trails that pass across the state including the California, Mormon Pioneer, Oregon, and Pony Express National Historic Trails. These trails truly defined the American West. It was a powerful experience to see where so many wagon wheels had passed over an area that the ruts are still visible today. I was able to visit a recently discovered American Indian battlefield, which made me reflect in a new way on the loss and displacement of the Lakota and Cheyenne. The guidelines included recommendations for engaging these communities in telling their own stories.

M) in Wyoming. The BLM manages several historic trails that pass across the state including the California, Mormon Pioneer, Oregon, and Pony Express National Historic Trails. These trails truly defined the American West. It was a powerful experience to see where so many wagon wheels had passed over an area that the ruts are still visible today. I was able to visit a recently discovered American Indian battlefield, which made me reflect in a new way on the loss and displacement of the Lakota and Cheyenne. The guidelines included recommendations for engaging these communities in telling their own stories.

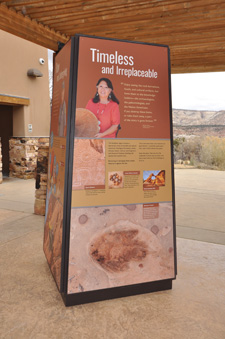

Anoth er of my favorite projects at the Escalante Visitor Center in Utah recently won an award from the National Association for Interpretation. I developed outdoor exhibits and an accompanying App that orients visitors to the amazing natural and cultural resources in the area. One of the main goals of this project was resource protection.

er of my favorite projects at the Escalante Visitor Center in Utah recently won an award from the National Association for Interpretation. I developed outdoor exhibits and an accompanying App that orients visitors to the amazing natural and cultural resources in the area. One of the main goals of this project was resource protection.

Can you tell us what you are working on right now?

I am working on an exhibit for Emory University that tells the story of student activism and civil rights from the 1960s onward. I am also working on an exhibit in Oklahoma that tells the story of Stanley Rother and the Tz’utujil people in Santiago Atitlan. The project focuses on social justice and development work happening in Guatemala from the 1960s onward and the complex political forces that drove the conflict there, ultimately leading the United Nations to condemn Guatemala’s ruling military party for “acts of genocide against groups of Mayan people.” The church in Santiago Atitlan, which is a focus for the project, was built by Spanish Franciscans in the mid-16th century.

How do you think the national historic preservation programs help your community?

Interpretation and historic preservation often go hand-in-hand. Many historic sites welcome visitors, and I think it is important for historians, archaeologists, and other preservation experts to work closely with interpretive planners and exhibit developers as they design public outreach. There is a natural tension, I think, between interpretation and preservation. Interpreters want to tell the stories of historic places with the goal of fostering stewardship. Sometimes, preservationists can be more interested in hiding these places from the public. I think there needs to be a balance between protection and public education. It is possible to love a place to death, and historic places do need to be protected, no doubt. But I think part of the point of preservation is for the public to know about these sites and to appreciate the stories these places embody. The national historic preservation program does an excellent job of researching and documenting historic sites, which must serve as the foundation of interpretation.

Do you have advice for novice preservationists?

Find a mentor. My most important professional lessons have not come from the classroom. They’ve come from working with mentors—people who have purposefully fostered my development.

How does interpretive planning/design help play a role in the preservation field?

Freeman Tilden defined interpretation as, “. . . an educational activity which aims to reveal meanings and relationships through the use of original objects, by firsthand experience, and by illustrative media, rather than simply to communicate factual information.”

I think the tendency at some historic sites is to convey too much information, and sometimes that information is less about what visitors want to know and more about what curators think visitors should know. Good interpretation should balance an institution’s goals—what it hopes to achieve—with what visitors want and expect from their visit. An interpretive plan should clearly define interpretation and preservation priorities and goals, as well as identify visitor characteristics and motivations to inform the development of effective exhibits and programming.

Content experts such as historians and archaeologists can provide valuable insights into interpretation, though it is important to remember that vast amounts of information must be interpreted for a general audience. This requires a different set of skills. Key messages need to be carefully crafted to link tangible objects and true stories about a site with universally understood concepts. Messages should follow storytelling conventions and need to be layered into a clear hierarchy that allows visitors, no matter their backgrounds or levels of interest, to grasp key ideas quickly. Thoughtful design can also incorporate ways for visitors to engage with and respond to the messages. In all cases, a good interpretive plan should provide ways for an organization to measure visitor satisfaction and to evaluate if institutional goals, which are frequently linked to preservation, are being achieved.

Read more Q&A stories about the preservationists in your neighborhood!