Fenella G. France, PhD, Chief, Preservation Research and Testing Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Fenella G. France is an international specialist on environmental deterioration to cultural objects. She has a PhD in textile science from the University of Otago (Dunedin, New Zealand) She focuses on non-invasive spectral imaging and other complementary analytical techniques. Additionally, she has developed a research infrastructure that integrates heritage and scientific data to advance linked open data and make data fair and accessible to a diverse range of users. Dr. France has worked on projects including World Trade Center Artifacts, Ellis Island Immigration Museum, and the 1507 Waldseemüller World Map. She collaborates with academic, cultural, forensic, and federal institutions. Currently Principal Investigator on a project to scientifically assess the condition of print materials in USA research libraries. Other international collaborations: Collections Demography, SEAHA doctoral training, Beast2Craft Biocodicology project, and CHaNGE – Cultural Heritage Analysis for New Generations.

What led you to your field?

There are a number of phone calls in my past…

When I was doing my PhD research, (my background is textile science) I got very interested in indigenous

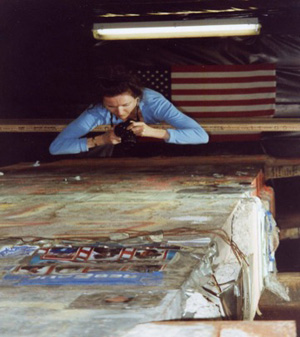

materials after being asked to give guidance on the condition of Maori cloaks Kaitaka (these are cloaks of finely woven Phormium tenax – a type of native flax, and highly prestigious to local iwi). I wanted to be able to give an answer by either taking no sample and being able to test non-invasively, or with an absolutely minuscule sample, since I knew the importance of these in my native country (New Zealand). Here began my fascination with how to preserve culture heritage of all forms while having no impact on the original. While still at the University of Otago I got a call about the Star Spangled Banner–the original American flag–they needed someone who had expertise in single fiber analyses to help preserve this American treasure. The project brought me to the United States and the Smithsonian Institution. It was followed by the 911 Trade Center Archives, Ellis Island Immigration Museum, Historic Houses, and then the Library of Congress.

How does what you do relate to historic preservation?

Everything that I have worked with over the past two to three decades has value to people and should be preserved to show open a window into our past. I wish that as a student I had spent more time learning

history, but I find that each item I work with has its own unique and special place in the world, and it brings such joy to both learn from the item, and then to apply my experience and expertise to be able to extend its life, and share these precious items with everyone. Not just the original item, but through visualizing and imaging, sharing more that you can see with the unaided eye.

Why do you think historic preservation matters?

With a background in textile science and preservation, I am deeply interested in the materiality of heritage, and the challenge that so often items that are used are more damaged than art works that are more revered. The “used” items seem so interesting to me–they retain a real feel for the world of the past and the people who have interacted with them–they allow us to touch our history and society. Preserving our history is so very important to be able to share the past with future generations, and without this understanding and link to where we come from, we cannot really anchor ourselves in the world. It’s so very, very important for knowing who we are, and where we belong; and for being able to see how we interconnect on a global scale.

What courses do you recommend for students interested in this field?

I feel very strongly that preservation requires extensive collaboration, and it brings together people with different expertise. Whatever a student feels passionate about–history, science, scholarship, research, data curation—these are all important aspects that each of us with different backgrounds and skills bring together to preserve our past. From a more pragmatic perspective, understanding how to interact with data is critical, computing skills, but storytelling to engage more interest and new audiences is the key to bringing the past alive and getting more people interested in history, and how to preserve it.

Do you have a favorite preservation project? What about it made it special?

All of my projects are special, but I would have to say that the Ellis Island Immigration Museum holds a special place in my heart, since it brings together so many aspects of humanity. The unique, special, and humble items that people brought with them to a new country that retained their link to their home countries, which they would use to forge a new life. And that the families donated these to share those stories, brought each family close and made that journey a special connection for everyone who visits and reads, sees those materials–clothing, spinning wheel, photographs–each item retains that connection to the past. It must have been a sudden change, scary but hopeful that reminds me of my own family journeying to New Zealand from Cornwall, with only the set of clothes they wore, their skills, and a burning desire to start a new life.

Can you tell us what you are working on right now?

I feel strongly about physical “things” and how much we can learn from that materiality. Right now I am

working on a project to help preserve the best volumes from paper-based print collections in the US https://nationalbookcollection.org/overview with the intent that this knowledge will help preserve small or at-risk collections that often do not have extensive funding, but that once gone, means that we have lost an important part of our history. There is always a feeling that someone else will preserve the last copy, but if we don’t take this seriously, the digital version will mean that all that we have is a static

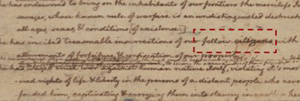

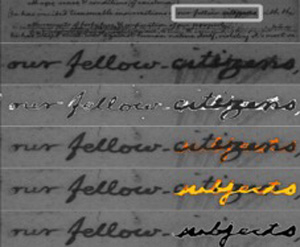

facsimile. My work with spectral imaging–which is a non-invasive process to reveal hidden text and information, has revealed unique insights into our past. Perhaps the most well-known is when I found that Thomas Jefferson has changed “subjects” to “citizens” in the rough draft of the Declaration of Independence: it showed how critically important preserving the original physical item is. We never know when new innovations and technologies will allow us to gain new insights into our past.

How do you think the national historic preservation programs help your community?

Right now it’s even more important for us to preserve community knowledge and collections–archives, buildings, people (oral histories)–because once they are lost, this leaves a hole in our collective awareness and comprehension of how we are in the world, what has come before us, and how we tell that story to future generations. National history preservation programs give voice to and show how important community is, the differences, the struggles, the joy, the perseverance.

Do you have advice for novice preservationists?

Start with what is familiar to you, and reach out to learn more. Don’t worry about how much you don’t know but keep striving. I have learned over the years two important lessons: 1) listen rather than speak to hear those

important lost stories, and 2) know that we are all always learning new things, if we are open and truly care.

The ACHP’s mission is “preserving America’s heritage;” can you give us an example of how your community is preserving its heritage?

I feel so very strongly about knowledge being available for all, so we have been working with new ways of visualizing data to share this online more effectively, so that anyone, anywhere in the world, can access collections to which they cannot now physically go visit. This becomes even more critical in the current global environment and is one of the ways we can create a strong understanding of other cultures. Moving together to preserve the physical collections, then making that accessible, opens a new lens into someone else’s community heritage, and world.

How do analytical chemistry and cultural heritage science play a role in the preservation field?

As you have seen, I am very focused on the materiality of cultural heritage objects, and by understanding the challenges for each different material–paper, parchment, inks, colors, photos, textiles, buildings, plants–we can slow down degradation and create an environment that allows these materials to be there for future generations. The science also means we can use a plethora of tools and methods to look into the past–document archaeology and forensics–to re-create the life of those objects, and bring this knowledge forward to explore our past in a different way. Whether we can reveal trade routes from specific material compositions, or from hidden information from trace particles of pollen, dust that tells a story, it is so very exciting to expose a new way of looking at these collections, and step back into the past.

Read more Q&A stories about the Preservationists in Your Neighborhood!